The Blind Leading the Blind – The School of Hard Knocks

by Kelly Brainerd

He stepped off the trailer soaked with sweat, nostrils flaring, screamin’ to high heaven. I said “Oh my!" He was dressed in the coolest, trendy Baker plaid dress suit. He was wrapped and then wrapped some more from the knees down, all four with quilts & bandages. His Mexican handler spoke softly to him, let him hop around a circle once or twice and away he went into a stall. The handler said his good-byes to him, wished him well, shook my hand and said, “ZULU".

I stood and watched the trailer drive away; in fact I watched them a long time until they were out of sight. I took some deep breaths and all the time I needed because in the barn was “Zulu”. At that point I didn’t even know what to do with him. He was the most magnificent horse I had ever seen. I had no idea what was under the Baker plaid. I wasn’t ready for what I was about to see. I took off his blanket and what I saw was the most beautiful markings I’d ever seen plastered over his back. I said to myself, “Zulu”.

The call recently came from my boss, “You have two weeks to find a place to put my blind horse." Zulu's diagnosis: Uveitis. Also known as “moon blindness” a term that was thrown around as well. I panicked. I hadn’t been a caregiver of a horse in eight years; my life didn’t include equines let alone a blind one. In fact I’d never taken care of a blind anything, let alone an animal that weighed over a thousand pounds. Besides wondering where I was going to investigate putting this horse I dove into everything the internet had to offer about blind horses.

I didn’t find tons of information but I found enough to have an idea how hard this was going to be. John Lyon’s Bright Zip kept coming up; I read everything John wrote about Zip. The most important piece of information I gathered was to keep your equine partner going. Keep doing the same things he is used to doing, keep him active. Because when a horse is used to a solid routine of training the worst thing you could do is decide he can’t do it anymore because he’s blind.

When Zulu arrived the information I received said he was a retired eighteen year old show jumper (I later learned he was actually ten). Although he looked to be not in bad shape for eighteen years old I would have never imagined he was only ten. His legs indicated this to be true as did the rest of his body. I was able to teach myself about wind puffs, bowed tendons, splints, results of continued use of a poor fitted saddle etc. With a good picture vet book in hand and Zulu’s busted up body I had a hands on subject to learn with; very informative.

He also came with some very interesting hardware on his feet that I was cautioned not to remove. He had egg bar shoes on all four; his back feet padded with wedges under his heels, because he had none. My horse experience didn’t include competitive jumping horses; I had never seen anything like this. I’ll never forget Zulu’s first farrier in the areaand what he said. The first time he picked up Zulu’s feet, he exclaimed he’d “heard something about this stuff in school but never saw it”. Zulu’s heels were gone and compensated for with rubber wedges so he’d have something to stand on.

Zulu was in the beginning stages of blindness, he could see from one eye as it hadn’t been affected yet and the right eye had begun losing sight. As most horses are walked on our right this worked out well for Zu because I was there to be his eyes on that side.

I learned bits and pieces of Zulus history like his age discrepancy, over a period of ten years, like his age discrepancy. After his jumping career was over he was purchased and boarded in a busy lesson/show barn. During his busy year round show life, he was traveled from Florida to New York. This show life had just come to a halt when Zulu changed hands, became privately owned, and used for personal lessons. His daily routine consisted of stall living, an hour turn out and being used in a lesson once a week.

His new owner was my boss. She had shipped Zulu home to her barn in the Catskills after a bad fall that broke her ankle. When she first told me about the accident, I asked her what her trainer said had likely caused the accident. Her trainer told her she needed to apply more leg, and that this was why the horse had failed his job in the ring. I told her to call a vet.

Yes, Zulu was suffering from uveitis, he was going blind. It was immediately asked that Zulu be removed from the jumper barn and that’s when he was moved three hours North to live out his retirement. His whole life had changed twice in a matter of months. He was facing huge adjustments to a new environment while progressively going blind.

Getting to know Zulu and gaining his trust happened sooner than I expected and that was a good thing. I didn’t have much to work with, only the research I crammed in and what common sense I could muster up to figure this out. Since horses are individuals it’s hard to know how each horse is going to react to becoming blind. Having already read that the best option was to keep your horse doing as much of his same routine as possible so that is what I did.

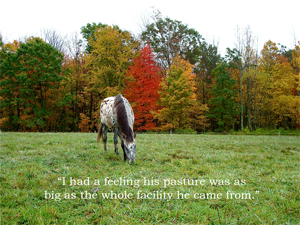

This was a near impossible request for Zulu. He had lived his entire life in busy show barns, he grew up with a groom, he lived in a stall with minimal turn out when he wasn’t traveling up and down the east coast on a busy show schedule. His polka dot beautiful self ended up on a sleepy horse farm in the Catskills. I had a feeling his pasture was as big as the whole facility he came from.

This was a near impossible request for Zulu. He had lived his entire life in busy show barns, he grew up with a groom, he lived in a stall with minimal turn out when he wasn’t traveling up and down the east coast on a busy show schedule. His polka dot beautiful self ended up on a sleepy horse farm in the Catskills. I had a feeling his pasture was as big as the whole facility he came from.

The weeks ahead were spent getting to know each other. This was an extremely proud animal; he was beautiful in every way. Although he had a good disposition most of the time, he had the capability to behave like a Thoroughbred by going from zero to a hundred in thirty seconds. He was a nervous horse and didn’t stand still. I learned this was mostly due to getting used to me and his new life. I also learned very quickly Zulu loved to be groomed and it was the one thing he would stand still for. I figured he had been groomed on a daily basis and started that routine immediatel. Sure enough, a hit. In our ten years we spent many hours together grooming. One day someone shouted at me, “You’re going to brush the spots right off that horse”. Well, that was fine by us both.

The other thing I quickly learned was that I was safer on his back than on the ground. When Zulu got nervous he became almost unmanageable. Trying to gain control on the ground once gone it was extremely dangerous.

I started riding Zulu very soon after a total melt down. A low flying helicopter appeared out of nowhere. It scared me too but Zulu was sure this thing was going to eat him. He proved to be much more controllable on his back. I think our bond started the first time I jumped on his back. I was able to ride him bareback with a halter and lead rope. That is how I started out riding him, our last days of riding weren’t much different only we dropped the halter and lead rope.

It’s hard to give advise about how to handle a blind horse as every horse is different. I can’t stress the importance of keeping your head in the game at all times. This is true with any horse but I can’t emphasize enough that you need to pay attention to what you’re doing. Besides the many obvious reasons you may think about, the most important you may not; if you compromise the comfort zone of the blind horse too many times you will never gain his trust. You will always have trouble handling him and that’s a safety issue for you and your horse.

You are his eyes, you must always watch where and what surface you are asking him to put his feet on. I watched one of my staff walk Zulu over a big patch of ice in the driveway. Zulu froze and became a thousand pound statue. I had to step in. Once Zulu realized it was me at the end of the lead Zulu carefully continued over the ice. After that he never trusted that staff member again and refused to deal with them.

Another important thing Zulu taught me was to always talk to him. Tell your horse what you plan to do with him. Always have a plan every time you touch your horse. I suggest that with any horse you verbally relay the plan to your horse. I read that horses see in pictures, so by telling your horse what the plan is, it will be embedded into your mind and your horse will get the picture. I believe this is true, I told Zulu every single thought I had and he reflected back confidence, honesty and true friendship. Zulu put his total trust in me.

I also suggest whenever you’re near the blind horse put and keep your hand on him, this way he always knows where you are at all times.

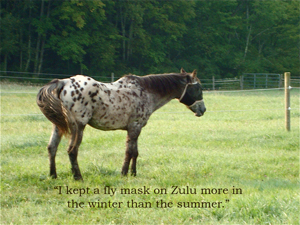

I kept a fly mask on Zulu more in the winter than in the summer. The fly mask protected his eyes from bad weather as well as from sun glare. The sun reflecting off the snow proved to be irritating to the eyes.

I kept a fly mask on Zulu more in the winter than in the summer. The fly mask protected his eyes from bad weather as well as from sun glare. The sun reflecting off the snow proved to be irritating to the eyes.

If your horse was turned out in a large pasture before he was going blind chances are good he can continue to manage in that same pasture. If you change his surroundings just be sure to spend plenty of time assisting him with getting acquainted in his new situation. If your horse has trust in you he will be comfortable where ever you are.

After being the care giver of a blind horse for ten years one would think I would be an expert on this. NOT! Since every horse is different it’s very hard to say how he may embrace his blindness but the four things I mentioned are a great starting point when managing a blind horse. You must really tune into him. Since his vision is compromised he will hone his other senses and become very aware of what’s going on around him. It was hard to tell that Zulu was blind if you didn’t know. He was a proud horse with so much to offer even though he was blind. He was perfect to ride as he would ask you where to go. He loved hanging out with his herd in huge pastures. He always found his hay and water and when he couldn’t I’d be the first to know because he would scream to high heaven until I came. That’s how I would know Zulu was having a problem.

Zulu lived a quality life despite his blindness, he learned to cope very quickly and he was a great trooper about it. I’ve heard horror stories of horses in great pain when they lose their eye sight. This wasn’t Zulu’s case. In the event of pain due to blindness there aren’t many options. The veterinary cost of complications due to blindness could get astronomical. There are many things to considerwhen taking on the care of a blind horse. If you embark on such an adventure, use good common sense, a heads up management approach and have patience; your equine friend will pay you back with appreciation tenfold.