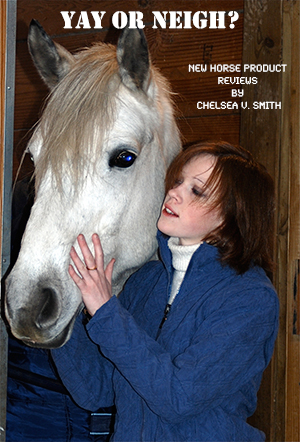

ALFRED MUNNINGS

By Amy McLaughlin

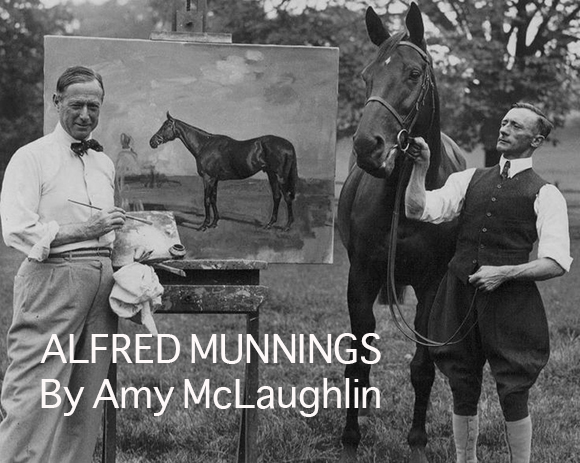

Alfred Munnings, the most successful and celebrated English horse painter since George Stubbs, was born in 1878 in Mendham in Suffolk, into a family that had lived in that area for centuries. He spent a happy and active childhood outdoors, in fields and stableyards, and among a varied assortment of animals. The world he knew as a boy was the ancient rural and agrarian one, shaped by the exigencies of nature and the rhythms of the seasons.

From humble beginnings as a miller's son, he rose to prominence, becoming an accomplished painter whose success brought him wealth, famous friends -- Winston Churchill was one -- and the presidency of the Royal Academy. The royal family and aristocracy, Rothschilds and Astors, commissioned work from him, and his paintings that now sell for record prices. Equestrian painters generally loiter in semi-exile at the margins of the art world. Their work, however well executed, is consigned to the genre of sporting art and does not usually attract much attention. Munnings' career was a remarkable exception.

Growing up, he was surrounded by all kinds of horses -- the draft horses that pulled wagons of corn to his father's mill, hunters, riding horses, and ponies. He recalls them encyclopaedically, the chestnuts, the dapple grays, duns and buckskins, the Suffolk punches, the Cleveland bays. Half a lifetime later, he remembered their names, personalities, and his experiences with them.

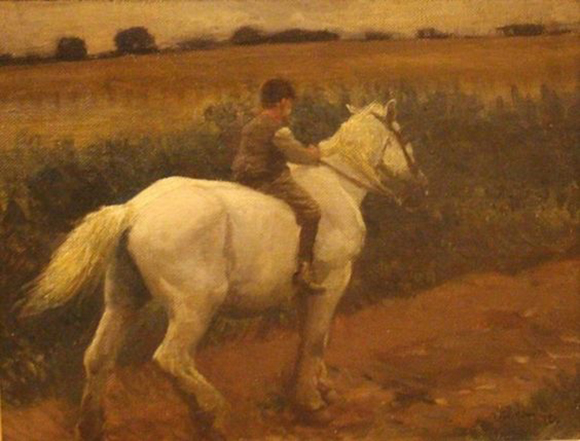

He began his education as a horseman early, largely left to his own devices with some minimalist advice: "I was told never to let go of the reins, so more than once I was dragged along on my stomach on the miry lanes."

His lifetime was contemporaneous with the profound, even violent, move towards an industrialized and increasingly urban society. Highways and railway lines were cutting across the fields and hedgerows of old England, and horses were being replaced by cars and tractors. He was a rueful witness to what was fading away:

"There were colts in numbers. These went out on summer nights on the large home meadow which sloped away from the lane in front of the house. Ancient, gnarled oaks stood on this pasture, and at the bottom end, near the gate, were a horse-pond, cart-sheds and tall elms...They were all around one, a common sight on every farm. Only now does an artist realize what is gone."

Munnings' body of work gives little evidence, though, of this rapid upheaval. The canvasses depict both the privileged class, enjoying their horses on vast estates in light suggestive of an endless afternoon, golden and benevolent, and humbler folk with their ponies and work horses. He painted similar subjects and scenes again and again, but in each work there is an exploration of light, texture and color so that passages of painting, magnified for closer study, appear as lush abstractions.

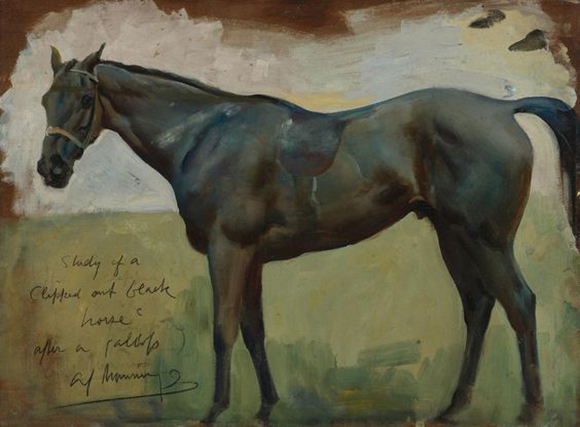

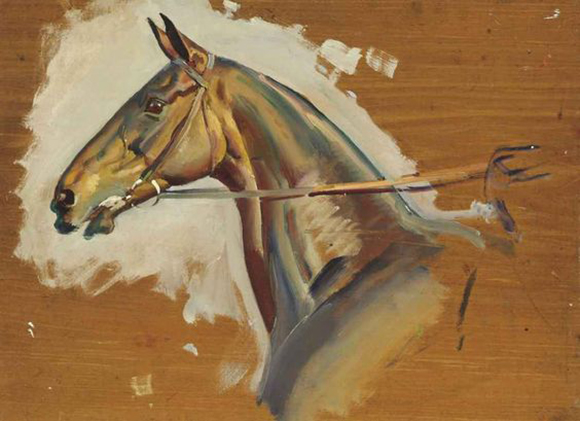

His interest in art showed itself early. Among the family's possessions was an oil painting of an earlier Munnings' horse, Orinoco. As a small boy, Munnings was fascinated by the painting, eyeing it surreptitiously when the family was gathered for evening prayers, curious about the way the texture of the horse's coat had been rendered, and how the artist had acquired his skills and gotten commissions. As this mature painting of a clipped horse shows, he successfully worked out both of these mysteries.

At fourteen Munnings was apprenticed to a lithographer in Norwich. He was a naturally gifted draftsman, and he was helped by the older, more experienced artists and an early patron, J.S. Tomkins, the owner of Caley's Chocolates, for whom Munnings produced many designs for posters and packaging, and of whom he wrote appreciatively, "he helped the whole course of my life". Tomkins gave Munnings one of his first painting commissions, a portrait of his father. "I did the old man posing on a garden seat surrounded by white phlox and Canterbury bells," recalled Munnings, "with his collie by his side". From the start, Munnings was highly versatile, painting landscapes, individual and group portraits before eventually turning almost exclusively to his favorite subject, horses.

He also enrolled in the Norwich Art School, and began a very typical academic training, starting with drawings from models and casts. At the age of 20 he had two paintings accepted to the Royal Academy's summer show. Tragically, shortly afterwards, an accident left him blind in one eye, when a branch hit him in the face as he lifted his dog over a hedge. He spent many weeks in a nursing home, his eyes bandaged. While there he learned he had won the gold medal at the Poster Academy. After his bandages were removed, he learned to paint with one eye, but would struggle all his life with depth perception.

His paintings are vibrant with the immediacy of directly observed nature. He absorbed a great deal from the work of the Barbizon painters and the Impressionists, the broad, free brushwork and juxtapositions, sometimes bold and sometimes more subtle, of contrasting colors. He has looked thoroughly at the shadows and half-tones, where seemingly improbable blues and yellows turn up frequently. Munnings travelled frequently, visiting galleries and museums all over Europe, absorbing lessons from very artists who are very diverse, and synthesizing them into his own singular and authoritative style. Even the most finished of his paintings, worked on in the studio, preserve this feeling of the outdoors, the woods and fields, stables and race meets, all of which were familiar territory to him from his rural boyhood and the preference he retained, as an adult, for country life.

George Stubbs left virtually no written record. There is no diary, and his sparse correspondence is limited to matters of business. His opinions and inner life are a mystery. Anyone curious about his attitude towards his subjects can find little, other than the paintings themselves, to enlighten them. His paintings are very beautiful, but there is no evidence of affection for the horses that were his most frequent subjects. The coolness with which he butchered and dissected them suggests that is unlikely.

In contrast, Munnings produced, at the age of about forty, a highly readable account of his childhood and his education as a horseman and artist. It is clear that his fascination was strong from his earliest days, that the vitality of his paintings springs from an abiding engagement with the animals he painted, and a thorough knowledge of what they were like and how they lived. Each one is remarkably individuated, its portrait painted as attentively as that of the riders and grooms. The artist has studied the animals' expressions and moods, the relaxed horse and rider ambling across a field, the nervous excitement at county fairs and races, the weary, patient draft horses being brought in after their day's labor in the fields.

The empathy he has for his subjects is evident, and Munnings' own candor about it, as a faculty too much lacking when he was young, is interesting. From his childhood memories, there springs a retrospective compassion for some of the animals he had known:

"We had a nanny goat too, which had a black stripe down its back. The goat pulled us in a little four-wheeled cart. We seemed to take it as part of our life, and thought little of it...But I have painted goats since in gypsy pictures, and have wished I had paid more attention to that kind creature which used to pull the youngest of us about."

Things that are done well can strike observers as having been easily achieved. Is there an equestrian who hasn't heard someone say, 'The rider just sits there'? ‘Munnings' sketches and paintings, with their fluent, confident brushwork, belie the struggle any figurative artist faces as they seek solutions to formal problems, translating what they see into a purposive sensual counterfeit that will hang together convincingly.

He insisted that the work of painting was hard -- 'entering the fray again' is a phrase repeated often in his autobiography -- perhaps reacting to assumptions that what he did was easy, achieved without effort. Munnings painted from nature, often taking hours out in the paddock as the nature in question became bored and restless with its modeling assignment. He considered that the hardest part of a horse's body to paint was the neck -- even as a mature painter, he found this complex, moving pyramid of bone and interlacing muscles a challenge.

And although photography had begun to influence painting, it had little impact on Munnings work. His first choice was always to paint the horse directly from life. Artists now often rely heavily on photographs, which may sometimes be all that is available. A skilled artist can compensate for what is lost, but there is always the risk of ending up with something stale and derivative. Use of these seductively convenient visual intermediaries can influence a painting greatly. Not only has the camera made many choices, flattening out the planes as it translates a three-dimensional image into a two-dimensional one, but there is also an enormous difference between a device and a human whose whole system is engaged, all of their senses responding to what is right there. This is essentially different from the experience of looking at photograph, and much of the strength of Munnings' work is the result of painting from life in the outdoors, in shifting weather and light, immersed in the scenes he is painting. He commented himself that "the truest and most satisfying form of landscape and figure painting has been achieved only through endless trouble taken, apart from actual technique" and "not difficult to tell which were done on the spot or from studies". When Munnings did work in the studio, he capitalized on the opportunity to create dramatic effects with controlled light.

One of his own first horses was a chestnut mare named Music. He traded an early landscape for her, and she became his first serious model.

"Music was a well-bred bay mare. My father's groom, Saxby, approved. ...Although she was hot, and shied at every bird flying out of a hedge, and though she was as quick as an eel, I spent many happy hours on her back. I was riding her from Harleston Swan on the night when, as I have related, she shied at the moon in a puddle and shot me off. I can see her now in the moonlight, patiently waiting in the road at the studio after my two-mile walk home. I was young, and she taught me a lot in riding and painting. With her I first began to paint a clipped-out horse on a winter day against a landscape background. The hours and hours this poor mare stood for me while I struggled with paint on canvas or in watercolour on paper were endless."

Munnings was a practical and grounded man, not inclined either to profound self-examination or weighing the great existential questions: "...in this wild, unspoiled country, all looking as it did centuries ago, I can take a horse and ride, or a long stick and walk away to some steep, bracken combe and lie down below all day on the close turf and hear the music of a stream running over the stones. Since I shall never know why I am here, so I shall never know when my time is best spent."

Having thus disposed of thorny philosophical matters, he happily spent his eighty years living and painting the agreeable life of a country gentleman. He was never moved to deviate from a course set early on. Munnings was contemptuous of modern art and was no revolutionary, despite his early years as a raffish bohemian. He famously dismissed Picasso and Matisse in a bombastic, and likely bibulous, after dinner speech at the Royal Academy. This speech is largely responsible for Munnings being remembered as a reactionary old fool, a Luddite among painters. His aesthetic judgment had no truck with Post Impressionism and Cubism, and the ideas driving these movements didn't interest him at all. But for what he did, he is hard to beat.

The many horses he had known over his lifetime, the 'friends of my destiny', he remembered fondly and with confidence that he had done right by them. '[They] are over the Styx now, but not enjoying a happier life, for they were happy with me. They could even choose their own paddocks...Looking back at my life, interwoven with theirs -- painting them, feeding them, riding them, I hope I have learned something of their ways. I have never ceased trying to understand them."